An Ode to Pen and Paper

Oof! This bi-weekly blog has not been so bi-weekly lately, has it? I’ve been busier and busier, from screenwriting (I just launched my animated series project website among other things!) to prose (I’m leading a workshop at the HippoCamp creative nonfiction conference this summer among other things!) to book review work (I reviewed a gorgeous poetry collection for PANK Magazine & am a new contributor for Feminist Book Club among other things!). And, don’t worry, that novel is still being perpetually revised and stressed over (in fact, the entire opening is being re-written! I’ve also started its screenplay adaptation! I am barely sleeping!).

Presumably due to the fact that all of this writing work happens on a computer screen (and so does half my piano teaching), I’ve been thinking a lot about the physicality of creating. Mostly, I’ve been craving it, and I’ve been trying to figure out why creating in the physical world matters so much to my creative well-being.

Letraset image from CreativePro

Art in the real world

I was born in 1990, so I’m part of the unique generation of kids who were the first to grow up with the Internet at our fingertips while still holding memories of the Before Times. I remember my graphic designer mom working at her drafting table with Letraset sheets full of letters. She’d order the sheets in different fonts and use them for design mock-ups instead of having to render the mock-ups by hand. But she still carefully burnished dry-transfer type one letter at a time—letters that had been formed into existence in the real world and had to be physically, individually touched and moved—which still seems pretty “by hand” to me. Today, of course, this all happens instantaneously on a computer.

I also remember being in awe of my United States Postal Service worker dad, who was the only adult I’d heard of whose employer was our actual country. From my dad, I learned to value the artwork that was a single stamp, the importance of legible numbers on an envelope and the unending creative possibilities of handwritten letters. I was amazed that I could write on a piece of paper, seal it in an envelope and trust complete strangers to respect, handle and deliver it. Physical mail is a collective effort and a long journey. A letter is sacred and protected—something worth waiting for. Comparatively, an email feels more like a quick zip into the void.

Another important part of my childhood was, of course, the piano—just about the biggest hobby a small child can get into in terms of literal physical space. Did you know pianos are made up of over 10,000 individual parts? Every time you depress just one piano key, over 100 parts move to get the energy from your finger to the string. One! Hundred! Parts! For the sound of one key! Now I teach piano to a generation of kids who frequently ask things like, “How do you turn it off?” and “Where does it plug in?” Some of my young students are mind-blown when they learn that all of the piano’s sound is created in the physical world. Digital instruments work for a variety of situations, but they just don’t offer the same feeling of physical connection—that energy that originates inside your body and travels through your arms, hands and fingers into a complicated structure of wood, felt and steel all to make a single sound.

Finally, I’ve been writing since I learned the shapes of all the letters, and it’s always been a pen-to-paper experience. I’ve always had a physical journal to write in, and most of my non-journal writing projects still begin on a sheet of paper. This process feels sacred to me. It’s like the mail that magically makes it through the world to its intended address, or those fonts that were carefully selected and purchased before being arranged as one part of a broader, already-thought-out design. Writing by hand feels more like I’m connecting with the “earth” of creating—making something in messy, slow, real life. It feels special.

To be clear

I am a big fan of computers and the Internet (you are reading this on my blog, are you not?). I even love social media! While the pandemic has been a trying experience in the best cases, I’m grateful for the strange opening to the world that occurred through the necessity of living life virtually these last two years. I wouldn’t have connected with screenwriters in Los Angeles and New York and Europe. I wouldn’t have taken fiction classes taught in Oregon, attended memoir workshops led in Brooklyn or watched book events hosted in D.C. In March 2020, life moved online overnight and I dove into the screen, excited about the literal world of opportunity that was instantly possible through my internet connection.

But, oof, it’s been two years, and I feel like I need to come up for air.

There are obvious pros to writing on a computer. It’s immediate. It’s to the point. It’s expected. You can revise as you go, get a task done expediently and move to the next one. Anything that’s going to actually go into the world needs to get onto a screen eventually, anyway. So why, if I am doing all of this writing, does it feel like I’m missing something important? What does pen-on-paper give me that the computer screen can’t?

Commitment

Anything you write with a pen on a sheet of paper is staying there. On a computer, there’s always the possibility of deletion. And if you’re a perfectionist, this constant possibility can turn the writing process into a nightmare. Writing something down on paper is committing your raw sloppy rambling ideas to the page—because you have no other choice. If I had only a computer screen to commit my raw sloppy rambling ideas to, they would never get out. And those ideas need to get out if I’m ever going to shape them into something more cohesive.

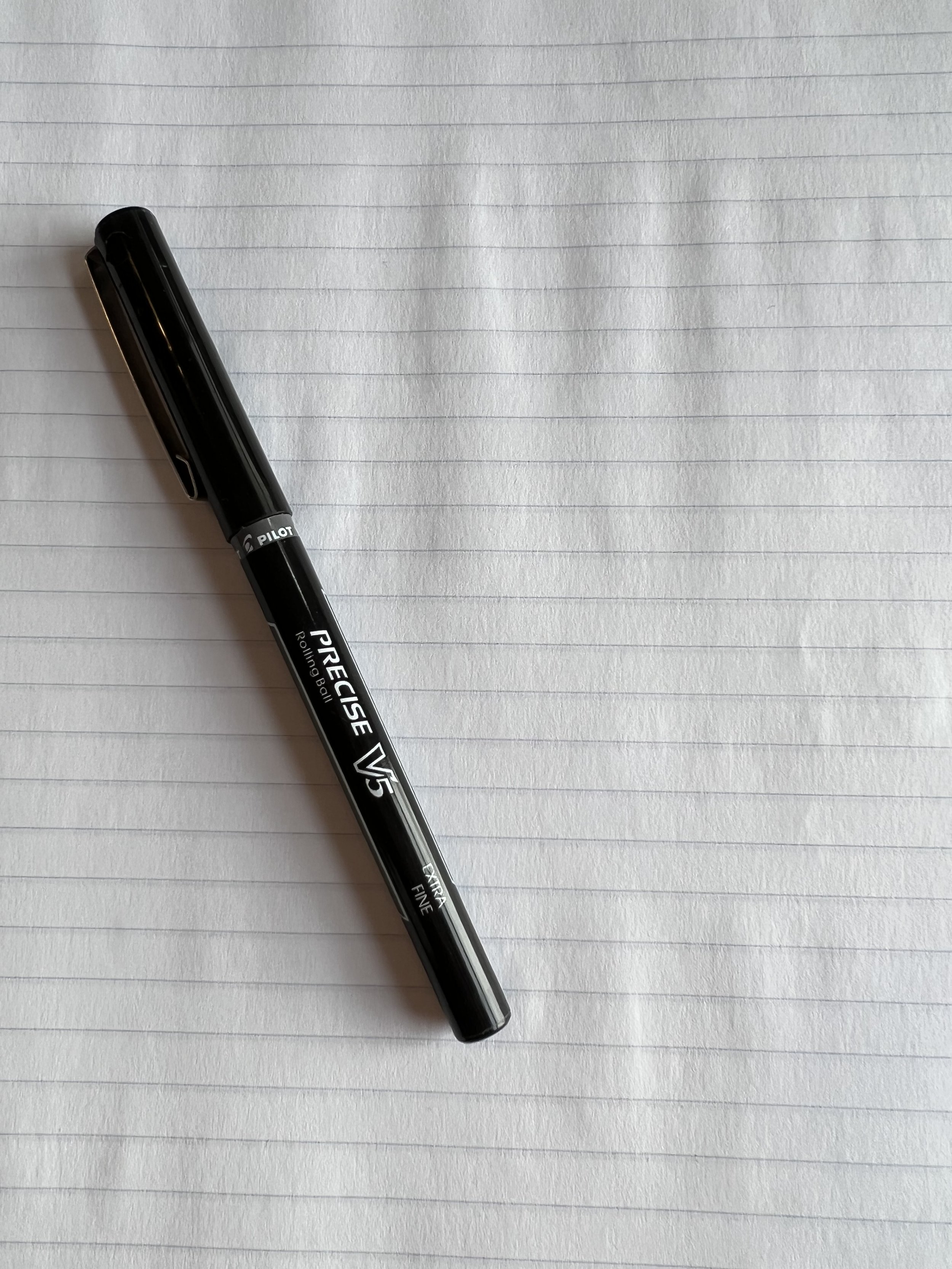

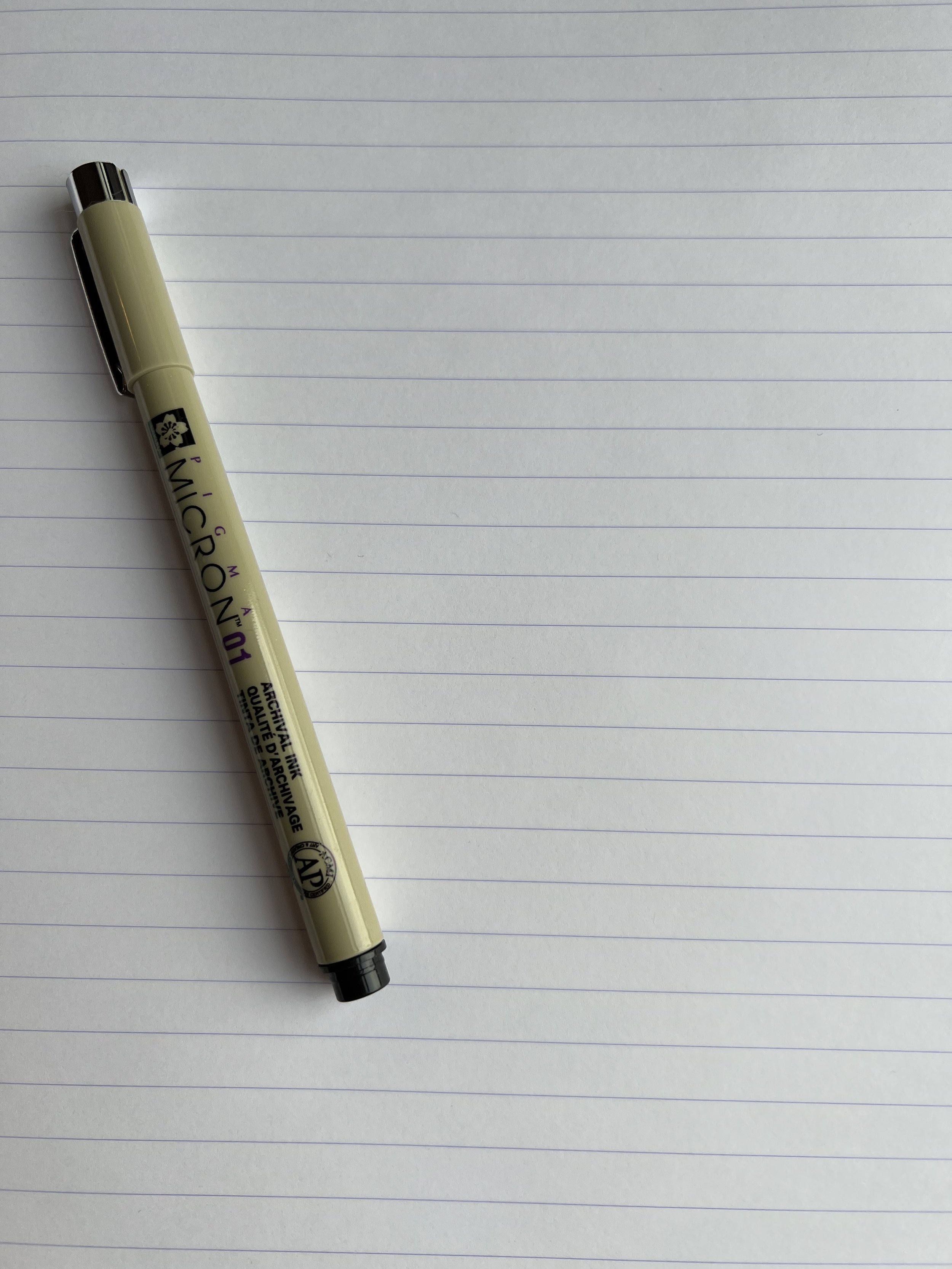

Physical rituals can also establish a commitment to work. I only use Pilot pens to write just about everything, and I’m fine with a cheap—as long as it’s large and spiral-bound—notebook to house the writing (see image on the left). However, creative nonfiction is especially personal and can be emotionally difficult to write. To make this process feel a little nicer to myself, I use better-quality materials (image on the right—so beautiful! so smooth!). It seems silly, but the small luxury of upgrading my pen and notebook is my way of validating the difficulty and importance of the work. It’s how I practice self-care during an emotionally vulnerable endeavor. Feeling the smooth ink on smooth paper is like giving a hug to myself.

Finally, what helps commitment to work better than a distraction-free zone?

Honesty

This whole idea that I have to commit to whatever I’ve written down (because there is no delete key) can also lead to more truth in my messy words. Going with the flow of whatever comes out of the pen unlocks the raw material in my system, which might have been carefully cultivated into something less embarrassing (and less honest) on the computer screen. Longhand writing is a safe space to make mistakes and be sloppy and say all the wrong things, which is essential to my creative process.

I have a long history of dealing with performance anxiety as a classical pianist, and I crave the coziness of making art in spaces where nobody is watching me. Anything I write down on paper is likely only ever going to be seen by me—a comforting feeling that goes back to my diary-writing days as a small child. Conversely, words-on-the-screen already feels like a performance. The screen is not my writing; the screen displays my writing. This already gives me the feeling that my writing is up on a stage for someone to look at. If I’m feeling nervous about how an audience may view my words, how honest will I really be?

Slowness

Obviously, writing by hand is bonkers slow compared to typing—but maybe this is a good thing. In the midst of my eager and hectic project work, I’ve been craving the ability to just sit still, reflect, and maybe do one small thing if it feels possible—and then maybe another, or maybe not. And either way, everything is okay.

Stephen King (who occasionally writes entire novels in longhand) writes about this slowness best: “It makes you think about each word as you write it, and it also gives you more of a chance so that you’re able — the sentences compose themselves in your head. It’s like hearing music, only it’s words. But you see more ahead because you can’t go as fast.”

He also describes the rewriting process after writing a first draft in longhand: “It seemed to me that my first draft was more polished, just because it wasn’t possible to go so fast. You can only drive your hand along at a certain speed. It felt like the difference between, say, rolling along in a powered scooter and actually hiking the countryside.”

This reminds me of slow practice in piano practicing, and how going slowly is crucial to every part of the process. I sometimes joke with students that half my job as a piano teacher is telling people to slow down. Why wouldn’t this apply to writing?

Meditation

“Hiking-the-countryside” slowness goes hand-in-hand with good meditative feelings. Meditation is about living in the present through connecting the mind and body—a state that can also be accessed by putting words to paper. I probably don’t need to tell you that meditative activities lead to feeling calm, peaceful, relaxed and maybe even inspired. Is it possible that handwriting just puts you in a different mental state than the computer screen does? As Quentin Tarantino—who handwrites all of his scripts—says: “I can’t write poetry on a computer, man!”

In her famous book on creativity The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron stresses the importance of "morning pages,” which are three pages of stream-of-consciousness longhand writing to be completed every morning. There are lots of reasons for doing morning pages, but the biggest one is meditation. Cameron writes: “The pages may not seem spiritual or even meditative—more like negative and materialistic, actually—but they are a valid form of meditation that gives us insight and helps us effect change in our lives…It is impossible to write morning pages for any extended period of time without coming into contact with an unexpected inner power.”

Connection

Connecting pen to paper allows me to connect with what’s in my mind, with what I’m feeling, and with my physical presence in the world. It may simply come down to the fact that I need to touch another real thing to feel real myself.

Throughout these two suddenly-very-virtual years, I’ve noticed that my desk has more and more rocks and crystals on it. (I realize I’m the one putting them there, but I like to think they’re multiplying on their own.) I’ve always been into rocks. I still have a handful of little stones that I first gathered when I was a kid. In recent years (maybe since my sister moved out to Los Angeles and I spent more time in that crystal-loving California culture), I’ve developed quite a collection of spheres and palm stones and crystals. I’m usually holding one in my hand while I’m in Zoom calls and writers’ groups. I love the feeling of a sphere’s weight and smooth polished surface. Whenever I glance down at a stone’s color or flash, I feel like I’m holding a little bit of magic. It reminds me that I’m still here in the real world; that I’m a raw sloppy rambling thing who can’t be perfect because perfect doesn’t exist and that’s okay.

A few days ago, I visited the Huntington Botanical Gardens with my sister in California. Big touch stones sat on concrete pedestals in the Japanese Garden. A sign explained that the stones have “the depths of color, hardness, density, and evocative forms prized in Japanese stone appreciation.”

The stones were big, lumpy, uniquely shaped. They were compelling for their naturalness. They felt cool to the touch, with surfaces smoothly polished from the touch of visitors’ hands. I thought about how simultaneously simple and complicated it is to exist at all as I read the sign’s most urgent message: “PLEASE TOUCH THESE STONES!” I did, and for a few moments, that connection was the only thing that mattered.

Jill G. Hall has advice on intuitive writing and the heart-hand connection.

This post is not actually an ode, is it? If I’ve disappointed you, here’s an actual ode (to the Midwest, of course) by Kevin Young.

A scene from my favorite movie about letter-writing: “What does it matter so long as our minds meet?”

Read more Wild Minds posts here.